Summary

- Four new anti-monopoly provisions have come into force in China

- They cover prohibition of monopoly agreements, abuse of dominance, merger control and abuse of administrative power

- The new provisions must be carefully examined as they could lead to some significant further burdens for businesses

- For example, China’s antitrust enforcement agency can call in certain transactions which fall below the notification threshold. The new provisions may significantly increase uncertainties in this area, and companies should take proactive steps to assess and prepare for potential notification

- Where needed, legal advice should be sought by companies as early as possible

On March 24, 2023, China’s antitrust authority, the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), released four provisions implementing the amended PRC Anti-Monopoly Law (AML) (中华人民共和国反垄断法), namely the Provisions for the Prohibition of Monopoly Agreements (禁止垄断协议规定), the Provisions for the Prohibition of Acts of Abuse of Dominant Market Position (禁止滥用市场支配地位行为规定), the Provisions for Reviews of Concentrations of Business Operators (经营者集中审查规定), and the Provisions for the Prohibition of Acts of Abuse of Administrative Power to Eliminate or Restrict Competition(制止滥用行政权力排除、限制竞争行为规定).

With these new provisions released and coming into force on April 15, 2023, companies have been provided with more guidance on how to comply with the amended AML. The four provisions will also have a number of impacts on companies doing business in China.

I. Provisions for the Prohibition of Monopoly Agreements (Agreements Provisions)

1. Postponement of the market share benchmark for “safe harbor” for vertical agreements

Previously, a 15% benchmark for “safe harbor” for vertical agreements was proposed in the draft of the Agreements Provisions. However, the version of the provisions as enacted takes a step back and postpones the specific market share benchmark, leaving it to be determined by the SAMR separately. As a result, companies still need to make a comprehensive evaluation of the competitive effects when imposing relevant vertical restrictions.

The Agreements Provisions also clarify that the scope of the entities for market share assessment includes “the parties to the agreement” (such as the brand and its distributor), not just the party that imposes the vertical restrictions. This is consistent with the usual approach when conducting competition analysis over vertical agreements.

2. More guidance on how “organizing” and “providing material assistance” in horizontal agreements should be determined

Under the Agreements Provisions, the subjective intention in “organizational” behavior is no longer emphasized, especially when an undertaking signs an agreement with multiple competing counterparties and serves as a channel that allows these competitors to communicate or exchange information. If a monopoly agreement is reached, the subjective intention of the undertaking will not be considered when determining “organizational” behavior. The Agreements Provisions also add a catch-all clause for the finding of “organizing” behavior, and leaves room for future enforcement.

The Agreements Provisions make it clear that when a third party provides necessary support, creates key facilitating conditions, or provides other significant help to competing firms in reaching a horizontal agreement, it is “providing material assistance”. When assessing “material assistance”, determining whether there is a “causal link” between the assistance and the impact on the elimination or restriction of competition, as well as whether the effect of the assistance is “significant” (which were proposed in the draft Agreements Provisions) are no longer required.

These changes indicate increased scrutiny of law enforcement agencies against so-called hub-and-spoke behaviors. Platform companies, companies with distribution channels, and those that might act as “hubs” should therefore pay more attention to the compliance requirements.

3. Leniency extended to cover “hubs” and individuals who face personal liability

The Agreements Provisions extend the scope of the leniency program to cover third parties who have organized or provided material assistance in reaching monopoly agreements (namely the “hubs”), as well as individuals who face personal liability under monopoly agreement violations(namely the legal representative, main responsible personnel and directly responsible personnel). As a result, these undertakings or individuals can also apply for leniency and provide important evidence, so as to get a fine reduction.

4. More detailed rules for conducting “regulatory talk”

“Regulatory talk” ( 约 谈 ) is a new mechanism stipulated in the amended AML. When an undertaking is suspected of violating the AML, the relevant enforcement agencies may summon the legal representative or responsible person of the undertaking for a meeting, and request him or her to propose improvement measures for the undertaking’s suspected violations.

The Agreements Provisions further specify the regulatory talk mechanism, including the content and requirements that the enforcement agencies can raise during the talk. It also specifies the obligations of the parties being subject to regulatory talk, including being cooperative in the rectification, proposing specific measures and deadlines to eliminate the harmful consequences caused by the conduct concerned, and submitting written reports.

5. Feedback on the results of the complaints can be requested

The Agreements Provisions make it clear that for real-name written complaints, upon the complainant’s written request, the enforcement agencies are able to provide feedback on the results after the investigation. In this way, real-name complainants are more incentivized, and will help enforcement agencies obtain more evidence in relation to suspected violations.

II. Provisions for the Prohibition of Acts of Abuse of Dominant Market Position (Abuse of Dominance Provisions)

1. “Self-preferencing” clause in the draft provisions removed

“Self-preferencing” by big tech (a company favoring its own goods in terms of display or ranking over other goods) has been a hot antitrust topic in China and other major jurisdictions. This could be a reason why the draft Abuse of Dominance Provisions formerly proposed a specific clause to regulate such behavior.

However, this “self-preferencing” clause has been removed from the finalized Abuse of Dominance Provisions.

Even so, big tech companies should be aware that the Abuse of Dominance Provisions contain another clause prohibiting abuse of dominance behaviors by making use of data, algorithms, technology, and platform rules. As the AML regulates abusive conduct in all forms, companies should make their assessment thoroughly and carefully evaluate whether any “self-preferencing” may still fall under the scrutiny of other types of abusive conduct.

2. More detailed rules stipulated for several abuse of dominance behaviors

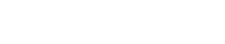

For several types of abusive behavior, the Abuse of Dominance Provisions provide additional factors to be considered in finding a violation:

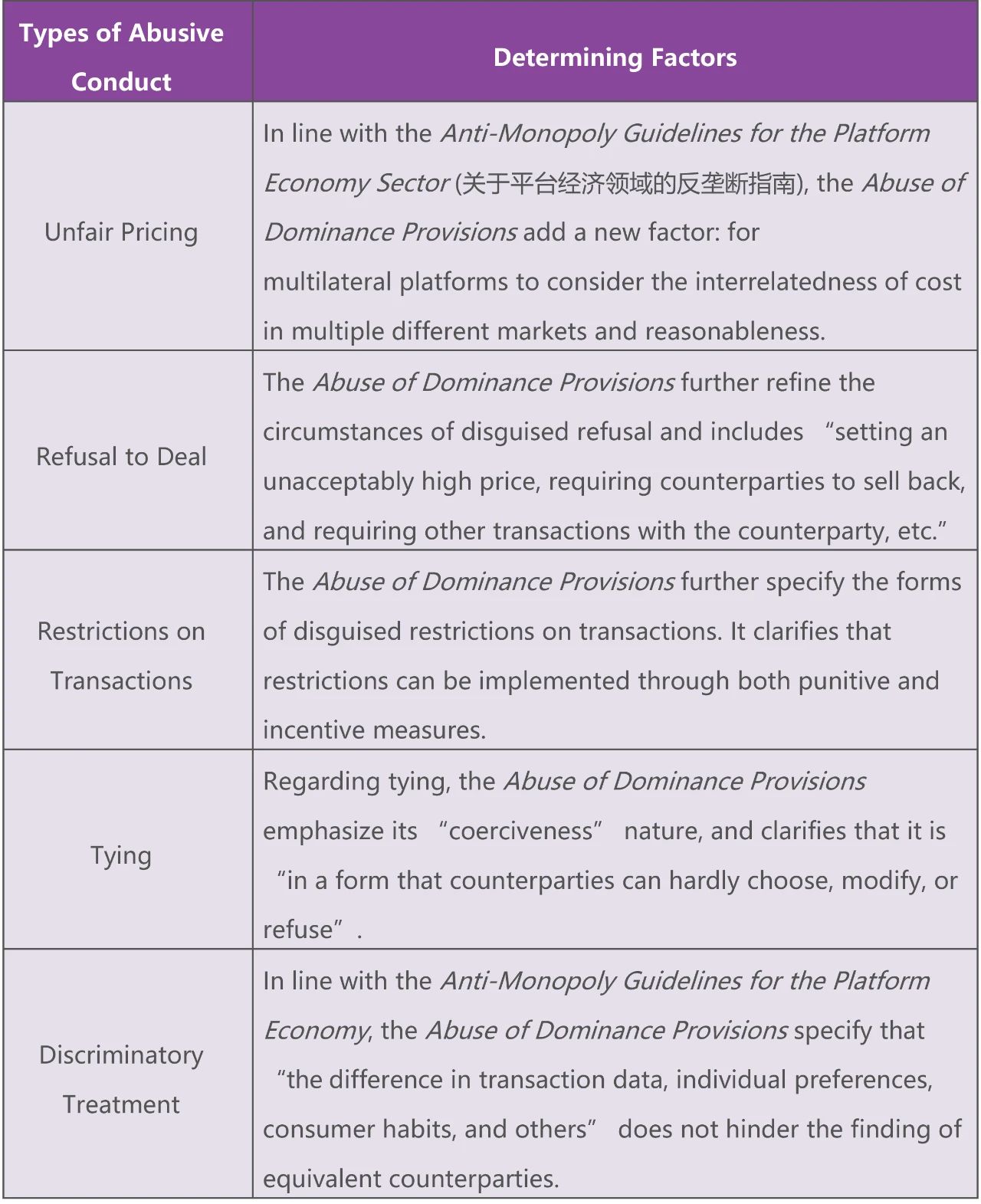

The Abuse of Dominance Provisions also refine the justifiable reasons for multiple types of abusive conduct, including:

In addition, the Abuse of Dominance Provisions also contain more detailed rules for conducting “regulatory talk” and makes it clear that feedback on the results of the complaints can be requested. These rules are consistent with the Agreements Provisions.

III. Provisions for Reviews of Concentrations of Business Operators (Merger Control Provisions)

1. Further elaboration on how to determine “a concentration of undertakings”, and the meaning of “joint control”

A merger control assessment always starts with determining whether there is an acquisition of control over the target business (“concentration of undertaking”). This generally involves analyzing factors such as the rules of procedure of the target’s governing and management bodies. The Merger Control Provisions incorporate more practical experience and provides guidance on the factors to be considered, including: (i) specifying that the composition, rules of procedure, historical attendance rates, and voting records of the shareholders meeting and other supreme management body, as well as the board of directors and other governing or management body should be taken into account; and (ii) composition of the supervisory board and its rules will not be relevant when making a merger control assessment. In addition, the Merger Control Provisions clarify that “joint control” refers to a situation where two or more undertakings have control over the target company or are able to exert decisive influence over other undertakings.

Though the draft Merger Control Provisions put forward a definition of control at the point when the acquirer can impact the business strategy and management decision of the target company, such as the appointment and dismissal of senior management, the budget and the business plan, the finalized Merger Control Provisions remove such special focus on these matters, which is consistent with the practice that a comprehensive assessment is always necessary to determine whether the control is or will be obtained.

Nevertheless, having veto right over these matters is still a strong indication of control.

2. Specification of the method for calculating the turnover of a third undertaking under “joint control” of undertakings concerned

The Merger Control Provisions provide clarity on how to calculate the turnover of a third undertaking under joint control of the undertakings concerned. According to the Merger Control Provisions, the turnover of such undertaking should be apportioned equally amongst the undertakings concerned. For example, if A and B are the undertakings concerned and jointly control a third party C, the turnover of C should be divided equally between A and B.

In practice, there has been much controversy about how to calculate a third undertaking’s turnover in such a scenario. Three methods have been proposed, including (i) apportioned to one undertaking concerned by choice; (ii) equally divided amongst undertakings concerned, or (iii) divided based on the percentage of share. The Merger Control Provisions have adopted the second method, which is consistent with the approach taken in European Union by the EC Merger Regulation. This helps to streamline the assessment of turnover across different jurisdictions.

3. Uncertainties in killer acquisitions might significantly increase

The amended AML empowers the enforcement agency to call in transactions which have or may have the effect of eliminating or restricting competition, even if they fall below the notification threshold (usually known as “killer acquisitions”). The Merger Control Provisions further stipulate that, if the concentration has not been implemented, the parties cannot proceed with implementation until notification is approved; and if the concentration has been implemented, parties must file notification within 120 days of receiving a written notice from the enforcement agency, and must also take necessary measures, such as suspending the implementation of the concentration, to minimize its adverse effects on competition.

As a result, transaction parties to killer acquisitions may face intensified risks under the new rules. Notably:

(i) filing timelines have been further shortened from 180 to 120 days upon receipt of notice from the enforcement agency; (ii) transaction parties must stand still until merger approval is obtained, even if the deal has been consummated; and (iii) transaction parties may also be required to take measures to reduce adverse effects on competition.

In order to better manage the risks in transactions below the threshold, companies are encouraged to consult antitrust lawyers early on to conduct risk assessments and formulate response plans. Exit plans including the breakup fees also need to be set with a more cautious mind.

4. When evaluating whether the transaction has been consummated, substance is over form and a higher duty of care is required in due diligence and the transition period

The Merger Control Provisions provide helpful clarifications for the benchmarks for “gun-jumping” violations. Registration of new shareholders in an M&A deal and obtaining the business license for the new joint venture in joint venture cooperation are obviously jumping the gun, and a number of other behaviors may amount to violations, including dispatching of senior management, participating in the business strategy and management, exchange of sensitive information, and substantial integration of business are also suspected violations. Undertakings jumping the gun would face a fine of up to RMB 5 million. In cases where there is exclusion or restriction of competition, a fine of up to 10% of the previous year’s revenue can be imposed.

These clarifications will help companies reduce “gun-jumping” risks. When companies negotiate the terms of transactions, especially those related to pre-closing arrangements, antitrust experts need to be involved so that potential “gun-jumping” risks, if any, can be assessed and properly reduced. In addition, the “clean team” mechanism should be used in every transaction, and the parties should not share competitive sensitive information beyond what is necessary for legitimate purposes such as negotiation and due diligence.

The Merger Control Provisions also make it clear that feedback on the results of the complaints can be requested, which is consistent with the Agreements Provisions and the Abuse of Dominance Provisions.

IV. Provisions for the Prohibition of Acts of Abuse of Administrative Power to Eliminate or Restrict Competition (Administrative Monopoly Provisions)

1. Further handling process of the administrative proposal has been clarified

Administrative proposals (行政建议书) are official letters issued by enforcement agencies to the superior administration of the party under investigation that is suspected of abuse of its administrative power. For example, when a municipal Department of Transportation is suspected of abuse of its administrative power,

the enforcement agencies may issue official letters to its superior administration, e.g. the provincial Department of Transportation, and request the superior administration to pay attention to the relevant situation and put forward handling suggestions.

The Administrative Monopoly Provisions require the enforcement agency, when issuing such administrative proposals, to set a time limit for the party under investigation to make rectifications. The party being investigated must submit a written report to both the superior administration and enforcement agency detailing its rectification measures, within the prescribed time limit.

This new requirement reinforces the urgency for the party under investigation to eliminate competition concerns. It may also incentivize companies that are suffering from administrative monopoly conduct to make reports to the enforcement agency, so as to protect their legitimate rights and interests.

2. The enforcement authority may have “regulatory talk” with administrations, and third parties also have the opportunity to participate

The Administrative Monopoly Provisions provide more details as to how the enforcement authority will carry out a “regulatory talk” with the administration (the investigatee). In order to ensure better regulation of administrative monopoly, the enforcement authority can invite the upper level administration of the party under investigation to participate in the “regulatory talk”. Media, industry associations, and experts can also be invited to participate.

The Administrative Monopoly Provisions also make it clear that feedback on the results of the complaints can be requested, which is consistent with the other three Provisions.

- Practices

- 反垄断与竞争法