The FSR entered into effect on 12 January 2023 and will be enforced as of 12 July 2023. Notification obligations under the FSR will become effective on 12 October 2023.

The FSR provides mechanisms for the European Commission (“Commission”) to assess the impact of third country (“foreign”) financial contributions in procurement procedures, in M&A transactions as well as in investigations undertaken at its own initiative. The FSR gives the Commission broad powers to assess whether such financial contributions amount to foreign subsidies that distort competition in the EU and, if so, to impose far-reaching remedies. Such remedies can include exclusion from a procurement process, the prohibition to conclude a certain transaction, repayment of the subsidies received, and obligations to share R&D or production capacity.

The practical impact of the FSR will be substantial. The FSR will:

The FSR could thus raise significant risks for large, internationally operating Chinese companies.

SCOPE OF THE FSR: DIFFERENT FROM THE ANTI-SUBSIDY REGULATION

Although the FSR concerns subsidies granted by third countries, its scope is different than that of the EU Anti-Subsidy Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/1037), a trade defense instrument which has now become familiar to many Chinese players following the imposition of countervailing measures on imports of several products from China in the last few years.

●The Anti-Subsidy Regulation applies to subsidized goods that are imported into the EU.

●The FSR empowers the Commission to examine subsidies granted by third countries in situations that would not be reviewable under the traditional trade defense instruments.

The key difference lies in the fact that the instruments established under the FSR cannot be used to address the importation of subsidized goods. A “subsidy” under EU trade defence rules is granted to entities producing goods outside the EU and has a detrimental impact on the EU market through imports of subsidised products. The concept of “foreign subsidy” under the FSR, on the other hand, covers subsidies benefitting entities which are active in the EU and does not relate to trade in goods in particular (but could relate to trade in services or any other activity).

OVERVIEW OF THE FSR: THREE NEW TOOLS

The FSR introduces three new “tools” the Commission can use to investigate – and potentially remedy – the distortive effects of foreign subsidies provided to companies active on the EU’s internal market. All three tools are relevant for Chinese companies which are active in the EU.

1. KEY CONCEPTS

“Financial contributions” that could amount to a “foreign subsidy” distorting the internal market

A foreign subsidy is deemed to exist “where a third country provides a financial contribution which confers a benefit to an undertaking engaging in an economic activity in the internal market and which is limited, in law or in fact, to an individual undertaking or industry or to several undertakings or industries”. This definition is informed by the concept of a subsidy within the meaning of EU trade defence law and WTO law as well as the concept of state aid in EU competition law.

The concepts of “financial contributions” which are subject to notification requirements, as well as the notions of “conferment by a third country”, a “benefit” and a “distorting” subsidy are addressed in further detail below.

The concept of “financial contribution”

The FSR’s definition of what constitutes a “financial contribution” is extremely broad. Financial contributions include any transfer of anything with economic value by any third country (at federal, state, or local level, and including entities whose actions are attributable to that third country) to a company that is active in the EU, including any member of the company’s control group. The benefits of a financial contribution do not need to be connected to a company’s EU operations in particular. Examples include:

This broad definition means that if there is a notification obligation or an ex officio investigation (see below), a company must collect information on financial contributions for all its subsidiaries and operations around the globe.

The concept of “conferring a benefit by third country”

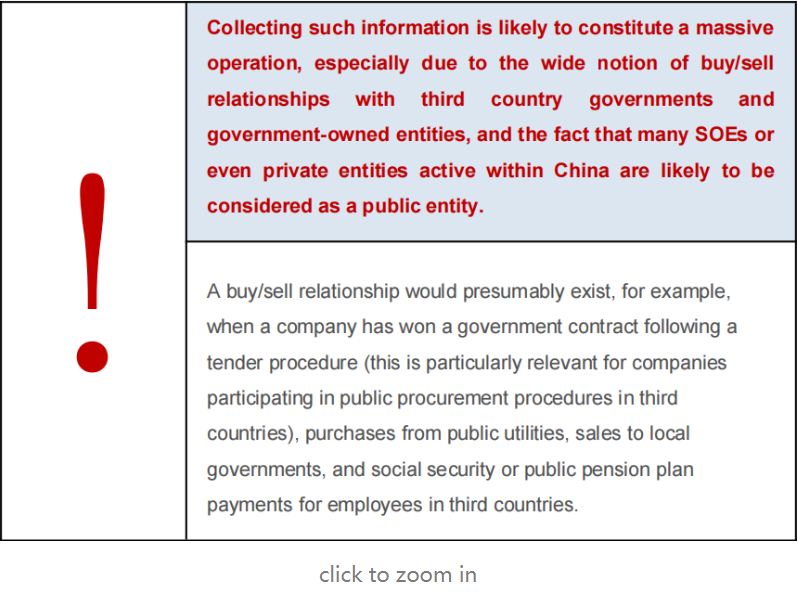

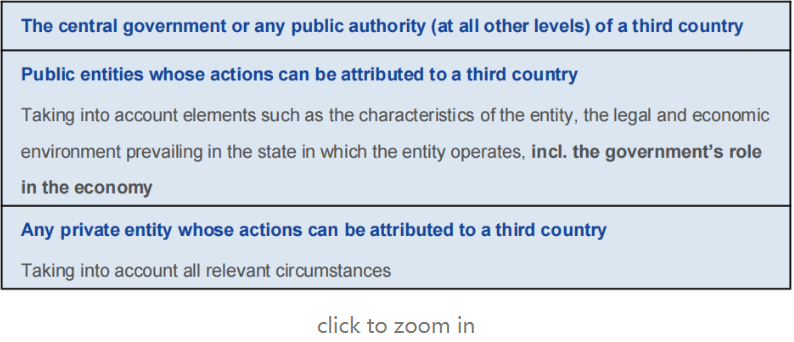

The concept of “conferring a benefit by a third country” under the FSR is also very broad. A financial contribution is considered to have been provided by a third country and thus be a “foreign” financial contribution if it is provided by an entity falling within any of the following categories:

The FSR does not require that the subsidy uses public resources: it is considered sufficient that the decision to grant the subsidy was taken (either directly or indirectly) by a public authority or entity. This is particularly significant in the case of China. In fact, considering the EU’s past practice in anti-subsidy investigations, Chinese SOEs, State-owned banks and many other private entities active on the Chinese market that have close ties to the Chinese government are likely to be considered as entities whose actions can be attributed to the government under the FSR.

In the context of anti-subsidy investigations, the Commission has set out criteria for the assessment of what constitutes a public body, including for example the “pursuance of public policy objectives which go beyond the normal remit of a private organization”, and “government control going beyond ownership”. Concrete factors taken into consideration by the Commission to determine whether a certain entity constitutes a public body include, amongst others, government ownership, influence on appointments, review of results and involvement in individual investment or business transitions by the government.

The FSR explicitly refers to the fact that “the government’s role in the economy” should be taken into account when determining whether a certain financial contribution should be considered as “foreign subsidy”. This suggests that the Commission is also likely to apply a broad reading of the concept of government or public entity in the context of the FSR, in particular when it comes to non-market economies, and China would likely be deemed as a non-market economy by the Commission based on its past practices in other related areas.

→Even though the FSR does not explicitly target subsidies from a specific region, it will thus have an especially significant impact on Chinese companies and investors due to the state’s prominent role in the Chinese economy, including the fact that such a high number of SOEs is active in China.

The concept of “benefit”

Under the FSR, a financial contribution is considered to confer a benefit to an undertaking if it could not have been obtained under normal market conditions. Depending on the type of financial contribution that was provided, this assessment involves relying on comparative benchmarks, such as the investment practice of private investors, rates for financing obtainable on the market, a comparable tax treatment, or the adequate remuneration for a given good or service for example.

In the context of anti-subsidy investigations concerning China, the Commission has taken the view that no adequate market benchmark was available within China to make such a comparison and to determine whether a benefit had been conferred. In such cases, the Commission relied on constructed or external benchmarks based on market conditions in third countries, making it more likely that a benefit is found to exist.

Considering the EU’s past practice in the context of anti-subsidy investigations, a benefit is thus more likely to be found to exist when the financial contribution at issue was provided by Chinese entities.

The concept of a “distortion” of the internal market

The FSR specifically targets foreign subsidies distorting the EU internal market. Such a distortion is deemed to exist “where a foreign subsidy is liable to improve the competitive position of an undertaking in the internal market and where, in doing so, it actually or potentially negatively affects competition on the internal market”.

Specific details of the test will be provided in future guidelines. The Commission will base its assessment of the harmfulness of a foreign subsidy on factual elements concerning the subsidy, the company and the market. The FSR already indicates that bailouts of companies in financial difficulties, grants to finance M&A activities, and general debt guarantees are most likely to be considered distortive.

The FSR also envisages that the Commission will then carry out a balancing test, weighing the negative effects of a foreign subsidy in terms of distortion on the internal market against the positive effects on the development of the relevant subsidised economic activity in the EU.

2. THE CONCENTRATIONS (M&A) TOOL

The first FSR tool is a mechanism to investigate whether mergers, acquisitions or joint ventures (“JV”) that qualify as “concentrations” [2]distort the internal market as the result of foreign subsidies received in the past three years. This concentrations tool allows for an ex-ante investigation of transactions where the acquiring party benefits from a foreign subsidy. The concentrations tool will operate separately from and in parallel with any merger control rules within the EU that may apply to the transaction, namely the EU Merger Regulation (“EUMR”) at EU level, or the merger control regimes of the EU Member States, as well as any other applicable ex-ante control mechanisms.

Notification obligations

Concentrations meeting the following thresholds are subject to the mandatory notification (and standstill) requirement:

→While these thresholds trigger the mandatory notification requirement, the Commission has jurisdiction to require parties to notify concentrations falling below the thresholds. If a notification is required under the FSR, the parties cannot close the transaction (standstill obligation).

Commission investigation and decision

The FSR gives the Commission the power to assess whether, as a result of a foreign contribution, there is a distortion on the internal market in the context of the concentration at issue.

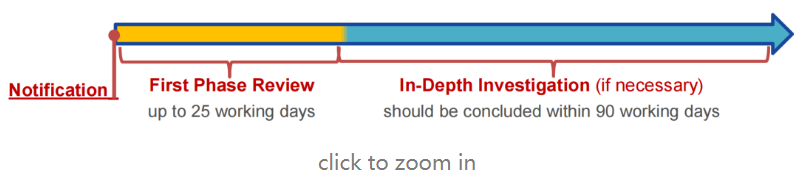

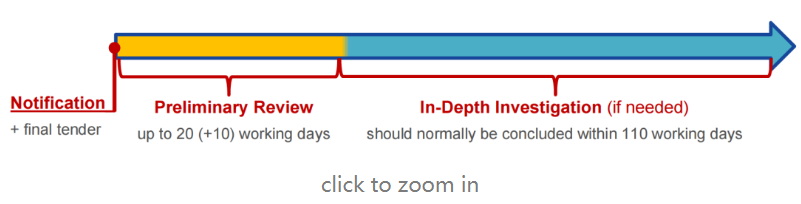

Deal closing timelines will need to take the FSR clearance process into account alongside any other global regulatory requirements, such as merger control processes. Helpfully, the FSR clearance timeline mirrors the EU merger clearance process, in that it includes a two-step process with statutorily set timeframes:

However, while these timeframes are theoretically aligned with the Commission’s Phase I and Phase II merger review process, in practice the two processes might diverge substantially, particularly if one process moves on to a second phase review and the other does not. We expect lengthy pre-notification periods (discussions of draft notifications until the Commission accepts a notification as complete and allows formal filing), and differences in the pre-notification phase can also result in divergent timelines.

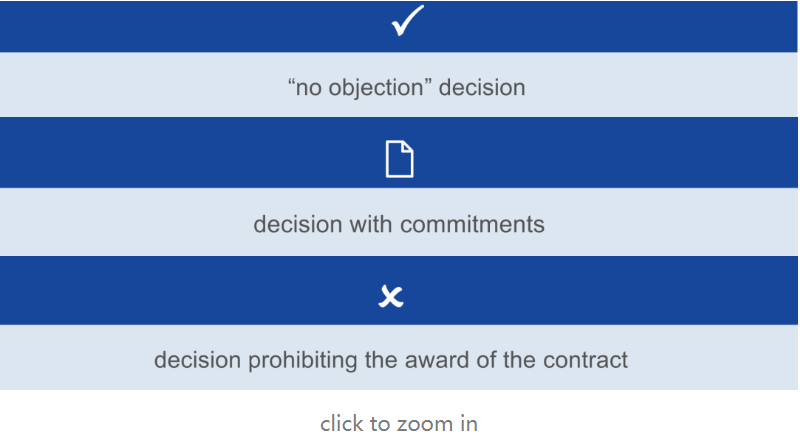

After conducting a review of a concentration under the FSR, the Commission may decide to:

In investigating concentrations under the FSR, the Commission enjoys powers similar to those exercised under the EU merger control process. Accordingly, the Commission can carry out inspections both within the EU and outside the EU (with the cooperation of third countries). It can also issue requests for information and impose interim measures and fines (including for failure to notify or to comply with the standstill obligation). But unlike in merger control, the Commission can assess the effects of a transaction even if the parties fail to cooperate. In such a case, the Commission is empowered – as in the trade remedies context – to rely on whatever facts are available to make its findings.

A review of a transaction under the FSR could be conducted in parallel with reviews under merger control laws (at EU or national level) and under foreign direct investment screeding tools (at national level).

3. THE PUBLIC PROCUREMENT TOOL

Under the second FSR tool, the public procurement tool, the FSR introduces an ex-ante obligation to notify a wide range of foreign financial contributions received during the past three years in the context of large public procurement projects in the EU.

Notification obligations

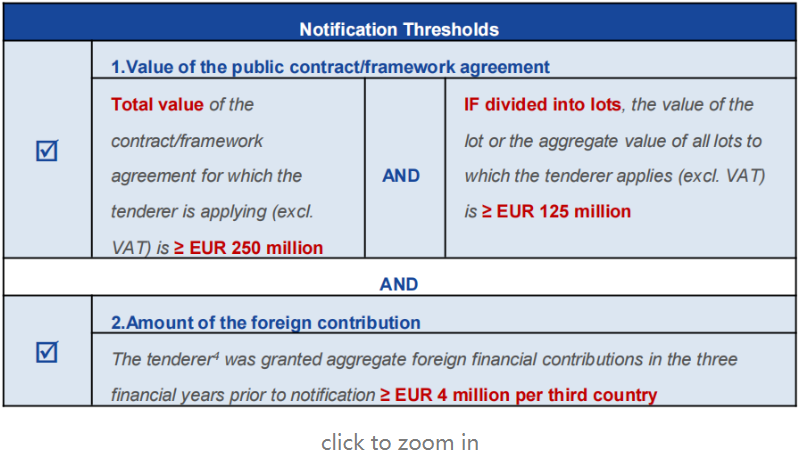

Tenderers in an EU public procurement procedure must submit a notification to the procurement authority if the following thresholds are met:

→Even if the second threshold is not met, tenderers must still declare all foreign financial contributions received and confirm that they are not notifiable.

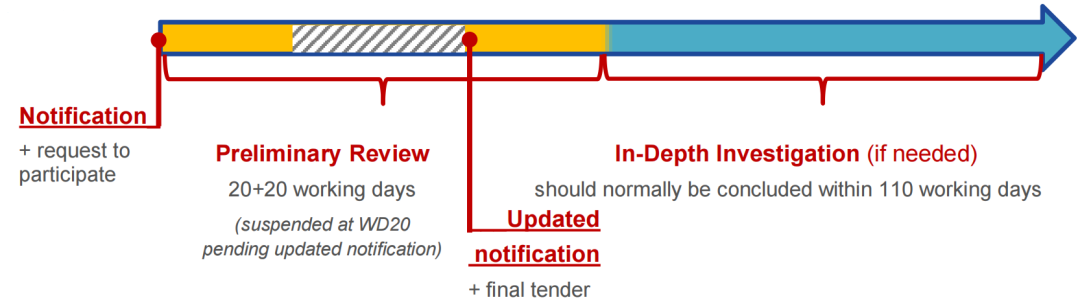

If a public procurement project is divided in prequalification and bid submission/award parts, a first notification must be made at the pre-qualification stage, and an updated notification must be made when the bid is submitted. The procurement authority will forward notifications/declarations to the Commission for review. Foreign contributions received by main sub-contractors must also be included in the notification.

If the Commission suspects that a tenderer might have benefitted from foreign subsidies in the three years prior to the submission of the tender, the Commission may request notification or start an ex officio review, though this review cannot result in the cancellation of the award decision or the termination of a public contract.

Commission investigation and decision

The notification timeline depends on the structure of the public procurement process at issue.

One-stage public procurement procedures – the tenderer must submit its notification/declaration immediately with its tender:

Multi-stage public procurement procedures – the tenderer must (i) submit its notification/declaration together with its request to participate; and (ii) submit an updated notification/declaration with its final tender:

As in the case of the M&A tool, lengthy pre-notification discussions likely will add substantial time to the above timelines. A standstill obligation applies during the Commission’s preliminary review and, if relevant, the in-depth investigation. This means that, pending the Commission’s assessment, all procedural steps in the public procurement procedure may continue, except for the award of the public contract. However, in certain circumstances the procurement authority may award a contract to a participant that submitted only a declaration even though the Commission’s review of notifications submitted by other bidders is still ongoing.

Following a preliminary review and – potentially – an in-depth investigation, the Commission may issue a:

The Commission may impose fines and periodic payments in case of specific violations (e.g., the violation of the standstill obligation or the intentional or negligent supply of incorrect or misleading information).

4. EX OFFICIO CONTROL OF ALL FOREIGN SUBSIDIES

Lastly, the FSR includes an ex officio control tool that allows (but does not require) the Commission to examine any alleged distortive foreign subsidies. The Commission can use this tool to investigate foreign subsidies in M&A or public procurement below the FSR notification thresholds, but more broadly whenever a recipient of foreign subsidies is active in the EU.

Under this tool, the Commission may, at its own initiative, investigate foreign subsidies received up to five years prior to the date of entry into force of the new Regulation if those subsidies distort the internal market after the new Regulation takes effect. If the Commission has a reasonable suspicion that foreign subsidies are distorting the internal market, it can carry out a full-fledged sector investigation. Considering that the Anti-Subsidy Regulation applies to subsidized goods imported into the EU, it can be expected that ex officio investigations will target primarily service industries.

In the context of an ex officio investigation, the Commission may examine information from any source, conduct preliminary reviews, and initiate in-depth investigations concerning alleged distortive foreign subsidies.

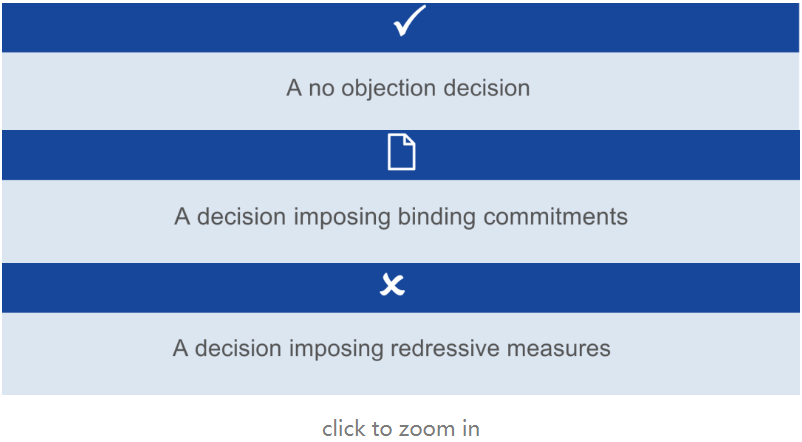

During an investigation, the Commission will consider several factors, including whether the foreign subsidy distorts the EU market, whether the undertaking under investigation offers commitments, and whether the distortion caused might be outweighed by the positive effects of the foreign subsidy.

Notably, unlike for concentrations, the scope of an ex officio review related to public procurements will be limited to awarded contracts and such a review may not result in the cancellation of a decision awarding a public contract, or in the termination of a public contract.

As is the case under the other FSR tools, at the end of an ex officio investigation, Commission may adopt the following decisions:

Furthermore, under the ex officio tool, the Commission may, under certain circumstances, adopt decisions ordering interim measures, it may require and request any information it deems necessary for its investigation from the parties involved, and it may conduct inspections of undertakings and associations thereof, both within and outside the EU.

IMPACT OF THE FSR ON CHINESE COMPANIES OPERATING ON THE EU MARKET

Many Chinese companies with global activities are also active in the EU and benefit from support from the Chinese government, Chinese State-owned enterprises (“SOEs”) or Chinese State-owned banks, in one form or another.

Planning for the FSR: steps to consider taking to reduce impact on business